(Page créée avec « In this tutorial, each category of home energy consumption is explained in detail. The topics of power and energy, which are relatively abstract, are addressed throughout... ») |

|||

| (75 révisions intermédiaires par le même utilisateur non affichées) | |||

| Ligne 40 : | Ligne 40 : | ||

|Step_Content=In this tutorial, each category of home energy consumption is explained in detail. The topics of power and energy, which are relatively abstract, are addressed throughout the text. | |Step_Content=In this tutorial, each category of home energy consumption is explained in detail. The topics of power and energy, which are relatively abstract, are addressed throughout the text. | ||

| − | + | Here is a brief explanation of these concepts: | |

| − | + | Power (P) is measured in watts (W) or kilowatts (kW) | |

| − | + | Energy (E) is measured in watt-hours (Wh) or kilowatt-hours (kWh) | |

| − | + | Power and energy are linked by time: power is the amount of energy per unit time. Power is therefore a rate of energy transfer. P x t = E | |

| − | + | Here is an example to illustrate these two closely related concepts: | |

| − | + | A cyclist pedaling slowly generates a power of 50 W. If they cycle for an hour, they produce an energy of 50 W x 1 hr = 50 kWh. If they pedal at this same slow speed for two hours, they produce an energy of 50 W x 1 hr = 100 kWh. | |

| − | + | The 16,000 kWh produced annually per household thus corresponds to 320,000 hours, or 36 years, of non-stop slow cycling. | |

| − | + | If we had to pedal to produce our own energy, how much time would it take? The game “Revolt” shows you the energy consumption of your everyday appliances in hours of cycling: http://la-revolt.org/ | |

| − | |||

}} | }} | ||

{{Tuto Step | {{Tuto Step | ||

| − | |Step_Title= | + | |Step_Title=Electricity and heat in the home |

| − | |Step_Content= | + | |Step_Content=More than three-fourths of energy consumed in the home goes toward heat production (home heating, hot water, and cooking). Half of electricity used in the household (50.4%) is for heat production. 81% of electricity is produced by nuclear power plants or fossil energy (gas, carbon, and oil). |

| − | + | The efficiency of nuclear power plants is around 30%. Here is a closer look at the electricity production and transport process: Fluid is heated to create pressure, and this pressure turns a turbine, which in turn feeds a generator to produce electricity. The resulting electricity is transported to homes, and there it is turned into heat. In terms of energy use, with three transformations and transport involved in the process, heating by electricity is not in our best interest. | |

}} | }} | ||

{{Tuto Step | {{Tuto Step | ||

| − | |Step_Title= | + | |Step_Title=Solar power |

| − | |Step_Content= | + | |Step_Content=The earth is subjected to significant solar radiation of an average power of 173 petawatts (1 PW = 1,015 W), which is 11,500 times the power consumed by humanity. |

| − | + | This solar power is being used a little more each day through the installation of photovoltaic panels. This type of panel has an efficiency of around 15%. There is another more technologically simple system that produces not only electricity but heat. These thermal solar panels have an efficiency of greater than 60%. This means that they produce four times the energy of photovoltaic panels over the same surface area. This is an attractive solution in light of the substantial heating needs in the home. | |

| − | + | On a clear day, the power of solar radiation on the surface of the earth is 1,000 W/m2. Even then, the intensity of solar radiation depends greatly on the season. In the summer, the sun is at its highest, or more perpendicular to the earth’s surface, and thus a greater density of rays is captured. On the other hand, in the winter, the sun is at its lowest. Not only is the angle of the sun affected by seasons, but so is day length. In Paris, the day’s length during the winter solstice is a little over 8 hours, while during the summer solstice, the day’s length is more than 16 hours. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Taking into account the power of the sun’s radiation and day length, the solar energy produced on a summer day is almost 6 times greater than that of a winter day (E = P x t). | |

| − | + | In order to harness this energy for thermal and electrical use, it is important to orient the panels at an optimum angle for the season, that is, more vertically in the winter and more horizontally in the summer. The fact remains that solar energy is always present, and a system that is very productive during the summer can always be used as a supplement in the winter. | |

|Step_Picture_00=L_nergie_dans_l_habitat_Soleil.jpg | |Step_Picture_00=L_nergie_dans_l_habitat_Soleil.jpg | ||

}} | }} | ||

{{Tuto Step | {{Tuto Step | ||

| − | |Step_Title= | + | |Step_Title=Heating: the ideal temperature |

| − | |Step_Content= | + | |Step_Content=It is natural that the temperature of a home is higher in the summer than the winter, and that we should dress appropriately for the seasons. Furthermore, it is not necessary for the house to be hot in order to live comfortably. The average temperature of a French home is 20 °C. The ADEME (the French Environment and Energy Management Agency) recommends a temperature of 19 °C in living areas and 16 °C in bedrooms. The difference in heating at 20 °C instead of 19 °C produces an energy overconsumption of 7%. |

| − | |||

| − | + | This can be partly explained scientifically using a simplified version of Fourier’s law, or the law of thermal conduction: | |

| − | + | J_th = -λ GradT = λ x ∆T/e | |

| − | Jth : | + | Jth : heat flow (W/m²) |

| − | λ : | + | λ : thermal conductivity (W/m/K) |

| − | ∆T : | + | ∆T : temperature difference between the two sides of the wall (°C or K) |

| − | e : | + | e : thickness of the wall (m) |

| − | + | According to this law, heat flow (that is, heat loss) is proportional to the difference in temperature. | |

| − | + | For example, if it is 12 °C outside and a house is heated at 18 °C: | |

| − | + | J_th1 = λ x (18-12) / e = λ x 6 / e | |

| − | + | If it remains 12 °C outside but a house is heated at 24 °C: | |

| − | + | J_th2 = λ x (24-12) / e = λ x 12 / e = 2×J_th1 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Regardless of the insulation used and its thickness, if it is 12 °C outside, then the heat loss will be two times greater at 24 °C than at 18 °C. | |

}} | }} | ||

{{Tuto Step | {{Tuto Step | ||

| − | |Step_Title= | + | |Step_Title=Heating: insulation |

| − | |Step_Content= | + | |Step_Content=On average over the year, heating represents two-thirds of household energy consumption at around 11,000 kWh. Considering that heating is only used during the cold season, or about six months of the year, it is a veritable “energy pit,” with about 60 kWh used daily when spread over this period. |

| − | + | A good insulation can reduce heating needs by 80%. There are several ways to insulate a house that vary widely in efficacy and cost. | |

| − | + | For example, exterior insulation protects a house from environmental cold and conserves solar energy within heavy construction materials if they are not covered in a thermal insulation. However, this method of insulation is expensive and requires a lot of work to install. And in any case, it isn’t via the walls that the most significant heat loss occurs. | |

| − | + | It is important to pay attention to the airtightness of a house, as it is useless to heat air currents even if the house is well insulated. Air currents come primarily from spaces between windows and doors and their frames. A foam seal will significantly limit these currents. | |

| − | + | Windows are responsible for 10 to 15% of heat loss. Closing the shutters or using heavy curtains will help you to avoid the need to invest in thicker windows. | |

| − | + | It is also important to pay attention to heat bridges, which are weak zones in the building envelope. In these areas, exterior cold is transmitted more rapidly into the interior of a home. The most significant heat bridges are found at junctions between the roof and the walls and between walls and window woodwork. These are the primary areas that should be insulated. | |

| − | + | Fourier’s law on thermal conduction is detailed in the previous step. Thermal conduction is the amount of heat that passes from one area to another depending on the type and thickness of the material separating the areas. This conduction depends on the thermal conductivity (λ) of a particular material. The weaker λ is, the more insulating the material is. According to the French regulation RT2012, a material is considered insulating if its thermal conductivity is less than 0.065 W/m/K. Here are some examples of materials that are used in construction: | |

| − | + | Material λ (W/m/K) at 20 °C | |

| − | + | Brick: 0.84 | |

| − | + | Cardboard: 0.11 | |

| − | + | Glass wool: 0.04 | |

| − | + | Straw: 0.04 | |

}} | }} | ||

{{Tuto Step | {{Tuto Step | ||

| − | |Step_Title= | + | |Step_Title=Heating: other options |

| − | |Step_Content= | + | |Step_Content=By this step, much has been improved: air currents have been blocked, the main heat bridges in the building envelope have been insulated, and the target temperature has been decreased by some degrees. Heating needs have thus been significantly reduced. Now, it becomes important to find a new source of heat, or at least an auxiliary source, to reduce direct (i.e., gas, oil) or indirect (electricity) consumption of fossil fuels. |

| − | + | Depending on the type of house and its location, it could be feasible to heat by burning biomass (i.e., wood, pellets, granulated wood) in a woodstove. Biomass stoves (a tutorial on this will be available in December) have an efficiency of greater than 80% and so are very economical in terms of fuel. | |

| − | + | Be aware, however, that heating by biomass is not synonymous with environmentalism. In fact, chimneys with an open hearth are one of the most mediocre forms of heating. Reheated air is sucked up the chimney, so the chimney only heats by radiation. The hotter the hearth gets, the greater the draw, and the more air is sucked from inside to the outside. An ordinary hearth can have a draw of 800 to 1,000 m3 of air per hour. The principal use of a chimney is thus reduced to ventilation. Ironically, with a chimney, the more it is heated, the colder the air gets (outside the zone of radiation). | |

| − | + | Furthermore, combustion in an open hearth is very incomplete. The fumes that escape through the chimney are unused hydrocarbons, resulting in a shortfall and further pollution. | |

| − | + | To summarize, the less fumes there are escaping from a stove, the better the efficiency of the combustion. The lower the temperature of the fumes, the more heat is available for the house. | |

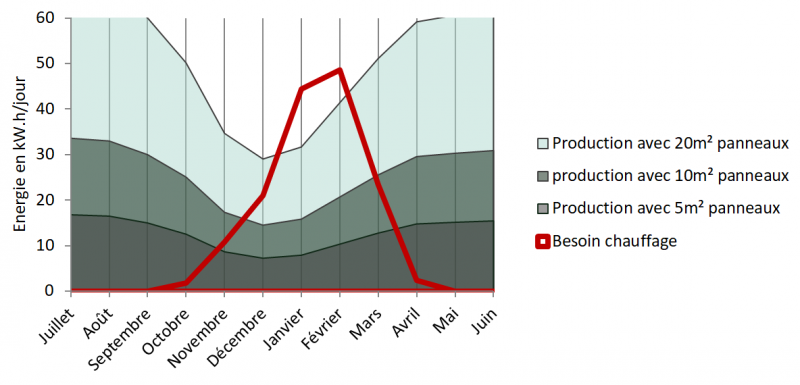

| − | + | In order to limit the volume of fuel (biomass, gas, oil) used for heating, it is possible to use solar radiation and its transformation into calories. In winter, the days are shorter and solar radiation is less powerful than in summer, but the available energy is still considerable. | |

| − | + | Taking into account the weather, from October to March (the period when heating is used) the sun provides more than 3 kWh/m2 per day in the south of France and more than 2 kWh/m2 in the north. Based on an efficiency of 60%, the energy captured by thermal solar panels would be 2 and 1.3 kWh/m2, respectively. | |

|Step_Picture_00=L_nergie_dans_l_habitat_Chauffage_vs_puissance_solaire.png | |Step_Picture_00=L_nergie_dans_l_habitat_Chauffage_vs_puissance_solaire.png | ||

}} | }} | ||

{{Tuto Step | {{Tuto Step | ||

| − | |Step_Title= | + | |Step_Title=Water heaters |

| − | |Step_Content= | + | |Step_Content=Hot water heating represents more than 10% of the total energy consumed annually in a home. The average household consumption is 1,700 kWh per year, or a little less than 5 kWh per day. |

| − | + | Just as with home heating, the first step to take is to well insulate the water heater, the hot water tank, and the pipes coming from it. A new hot water tank of 200 liters has a standing loss of more than 1 kWh per day. Standing loss is the energy related to the decrease in the water's temperature before it is used. So, 20% of the energy consumed daily by this new hot water tank is lost. Insulating the hot water tank will preserve some of this energy. A hot water tank should be cool to the touch; if not, it is simply a radiator and is losing energy in relation to its primary function. | |

| − | + | In previous steps we looked at the benefits and limits of thermal solar heating. Home heating needs are inversely proportional to the energy provided by the sun. For water heating, the situation is different: needs are similar throughout the year and are 13 times less than what is needed for home heating in the middle of winter. | |

| − | + | The operation of a solar water heater is simple: a heat-carrying fluid passes through insulated tubes that are exposed to the sun. The sun’s radiation heats the fluid, and when the temperature of the fluid exceeds that of the hot water tank, a thermostat opens a circulation valve. The fluid then transfers its calories to the water in the tank. | |

| − | + | The water in a hot water tank is heated during the day by the sun. Water has a good thermal inertia, so it will maintain its temperature at night if the tank is insulated. | |

| − | + | Thermal solar systems generally have an efficiency greater than 60%, meaning that if the sun radiates 1,000 W/m2, a solar water heater of 1 m2 will generate at least 600 W of heat. | |

| − | + | Given the average amount of sunshine in France, 4 m2 of panels is enough to cover daily hot water needs year-round. 3 m2 of panels will cover daily needs 90% of the year except for December, and 2 m2 will cover needs during the hottest half of the year. | |

| − | + | In any season, it is possible to have multiple consecutive days without sunshine, in which the water will remain cold. Solar hot water systems are generally paired with electric systems that make up for the deficit during these long cloudy periods. | |

| − | + | A low-tech solar hot water system will be documented by the Low-tech Lab in 2018. | |

|Step_Picture_00=L_nergie_dans_l_habitat_chauffe-eau.png | |Step_Picture_00=L_nergie_dans_l_habitat_chauffe-eau.png | ||

}} | }} | ||

{{Tuto Step | {{Tuto Step | ||

| − | |Step_Title= | + | |Step_Title=Cooking |

| − | |Step_Content= | + | |Step_Content=Cooking represents about 6% of energy consumed. This is a little less than 1,000 kWh annually or about 2.5 kWh per day. |

| − | + | Overall, from an energy consumption point of view, cooking with gas is the most attractive option. The efficiency of a gas cooker is 60% compared to 90% for induction cookers. However, as seen in the introduction, mains electricity is produced using heat. Taking into account the 70% loss of the power plant and the grid, the energy efficiency of induction cookers falls to 27%. | |

| − | + | Mains gas is a natural gas called methane (CH4). It is possible to produce methane on a small scale from organic waste via anaerobic composting. Domestic systems that produce methane are called biodigesters. | |

| − | + | To reduce energy consumption in cooking, two simple solutions can be put in place: pot skirts and Norwegian pots. A gas cooker loses a good portion of its energy in heating the air around the pot. A skirt will concentrate the heat of the fire on the spot that needs to be heated. The skirt also insulates the pot, which limits heat loss during and after cooking. This is the same principle with the Norwegian pot, which is used particularly for longer cooks. Once the food has reached the needed temperature, it can be taken off the heat and placed in a well-insulated enclosure. The heat will decrease very gently, possibly over hours, allowing cooking to continue without consuming additional energy. For these two solutions, tutorials will soon be available. | |

|Step_Picture_00=L_nergie_dans_l_habitat_cuisson.png | |Step_Picture_00=L_nergie_dans_l_habitat_cuisson.png | ||

}} | }} | ||

{{Tuto Step | {{Tuto Step | ||

| − | |Step_Title= | + | |Step_Title=Specific energy |

| − | |Step_Content= | + | |Step_Content=Specific energy is energy use dedicated to lighting, household appliances, office equipment, and hi-fi. It is the only category of energy use in which the need is for electricity; all other energy used in the home is for heating needs. Currently, this category represents 16.6% of energy consumed. This is a little less than 2,700 kWh per year or about 7 kWh per day. |

| − | + | With the mass arrival of energy efficient bulbs and LEDs, energy consumption related to lighting has greatly decreased. And yet, the consumption of specific energy has doubled since 1990. This is due to the growing number of electric devices such as telephones and computers that are now part of daily life. | |

| − | + | To limit specific energy consumption, it is important to not increase the number of devices in the home. Furthermore, devices that are not currently in use are often in sleep mode, which consumes slightly less than 1 W. This 1 W per year used by sleep mode is equal to the amount of energy needed for 4 days of cooking. The energy consumed by multiple devices in sleep mode can be significant. | |

| − | + | And finally, there is a phenomenon that may be invisible at an individual level but has a large impact on a national scale: the electric consumption in the evening when a large part of electricity needs are concentrated within a few hours. At that time, everyone returns home and turns on all of their devices (televisions, computers, washing machines, ovens, etc.). The demand is such that the national consumption sees a veritable peak during this period. Since little to no energy can be stored, power plants must provide this energy in real time. French power stations are sized based on this energy demand at the start of the evening. | |

| − | + | If electricity consumption were spread out over the day, many electric power plants could be closed. In answer to this need, it is possible to program certain devices to run during the night, or even better, during the day to take advantage of solar photovoltaic panels that are becoming increasingly present. | |

|Step_Picture_00=L_nergie_dans_l_habitat_E_Sp_cifique.png | |Step_Picture_00=L_nergie_dans_l_habitat_E_Sp_cifique.png | ||

}} | }} | ||

{{Tuto Step | {{Tuto Step | ||

|Step_Title=Conclusion | |Step_Title=Conclusion | ||

| − | |Step_Content= | + | |Step_Content=Energy consumption in the French household is significant. The first step in individual energy transition is not to change the source of energy and/or the scale of production. The installation of photovoltaic panels or windmills is not economically and ecologically impactful if there is not a significant reduction in energy consumption first. |

| − | + | However, reducing your consumption does not mean depriving yourself of comfort; it means making your home more efficient. Above all else, efficiency is limiting losses. Since more than 70% of energy is consumed in heating, losses can be limited by well insulating the home. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Once these losses are reduced, then it is possible to look for solutions that use less power. The alternatives are numerous and attractive, both low-tech and conventional: | |

| − | + | Woodstove | |

| − | + | Solar heating | |

| − | + | Solar water heater | |

| − | + | Bioclimatic architecture | |

| − | + | Wind power | |

| − | + | Solar panels | |

| − | + | Biogas | |

| − | + | Norwegian pot | |

| − | + | Pot skirt | |

}} | }} | ||

{{Notes | {{Notes | ||

| − | |Notes= | + | |Notes=https://www.connaissancedesenergies.org/fiche-pedagogique/mix-energetique-de-la-france |

| − | + | http://www.statistiques.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/energie-climat/r/consommations-secteur-tous-secteurs.html?tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=21060&cHash=4168b27f68d9955400f2c25b0419095f | |

| − | + | https://www.ecologique-solidaire.gouv.fr/collection-datalab | |

| − | + | http://ines.solaire.free.fr/gisesol_1.php# | |

| − | + | https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conductivit%C3%A9_thermique | |

| − | + | https://www.connaissancedesenergies.org/fiche-pedagogique/mix-energetique-de-la-france | |

| − | + | https://www.e-rt2012.fr/explications/conception/explication-architecture-bioclimatique/ | |

| − | + | http://www.solaire1300.ch/f/technologie-solaire/rayonnement-solaire-delivre-par-heure.asp | |

| − | + | http://www.ademe.fr/particuliers-eco-citoyens/habitation/renover/isolation/isolation-toit-murs-planchers | |

| + | |||

| + | English translation : Brianna Lale. | ||

}} | }} | ||

{{PageLang | {{PageLang | ||

Version actuelle datée du 8 novembre 2022 à 10:35

Description

How to have energy-efficient homes

Sommaire

Sommaire

- 1 Description

- 2 Sommaire

- 3 Introduction

- 4 Video d'introduction

- 5 Étape 1 - Energy consumption in France

- 6 Étape 2 - Glossary

- 7 Étape 3 - Electricity and heat in the home

- 8 Étape 4 - Solar power

- 9 Étape 5 - Heating: the ideal temperature

- 10 Étape 6 - Heating: insulation

- 11 Étape 7 - Heating: other options

- 12 Étape 8 - Water heaters

- 13 Étape 9 - Cooking

- 14 Étape 10 - Specific energy

- 15 Étape 11 - Conclusion

- 16 Notes et références

- 17 Commentaires

Introduction

Youtube

Étape 1 - Energy consumption in France

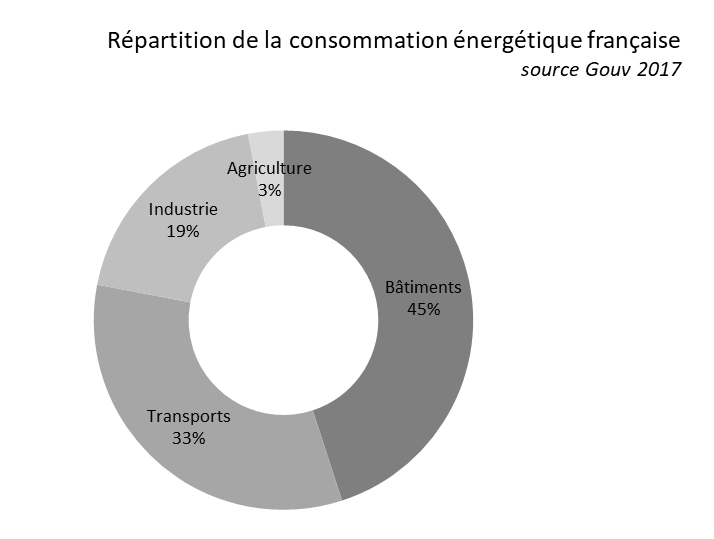

In France, buildings account for 45% of the total energy consumed, followed by transportation (33%), industry (19%), and agriculture (3%). Two-thirds of the energy consumption in this category comes from housing and one-third from service sector buildings.

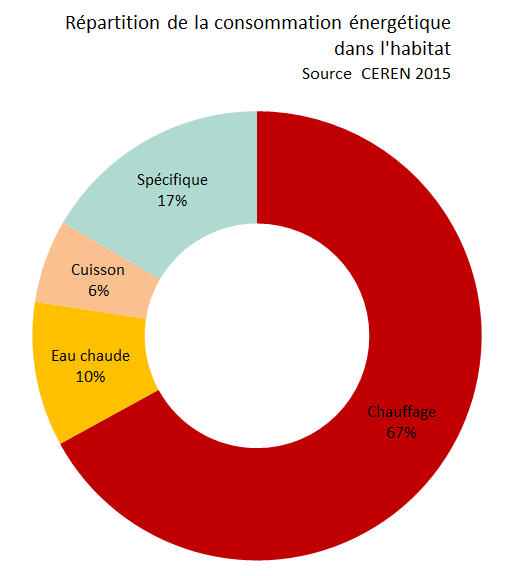

Within the home, in 2013, 67% of consumed energy went toward heating the home, 10.4% toward heating water, and 6% toward cooking. The remaining 16.6% was used for lighting, household appliances, office equipment, and hi-fi, all of which is grouped under the term “specific energy”. The 16,000 kWh consumed by each household costs just over €1,700 per year.

In France, residential heating accounts for a larger portion of the total energy consumed (20.1%) than does industry (19%).

Étape 2 - Glossary

In this tutorial, each category of home energy consumption is explained in detail. The topics of power and energy, which are relatively abstract, are addressed throughout the text.

Here is a brief explanation of these concepts:

Power (P) is measured in watts (W) or kilowatts (kW) Energy (E) is measured in watt-hours (Wh) or kilowatt-hours (kWh)

Power and energy are linked by time: power is the amount of energy per unit time. Power is therefore a rate of energy transfer. P x t = E

Here is an example to illustrate these two closely related concepts:

A cyclist pedaling slowly generates a power of 50 W. If they cycle for an hour, they produce an energy of 50 W x 1 hr = 50 kWh. If they pedal at this same slow speed for two hours, they produce an energy of 50 W x 1 hr = 100 kWh.

The 16,000 kWh produced annually per household thus corresponds to 320,000 hours, or 36 years, of non-stop slow cycling.

If we had to pedal to produce our own energy, how much time would it take? The game “Revolt” shows you the energy consumption of your everyday appliances in hours of cycling: http://la-revolt.org/

Étape 3 - Electricity and heat in the home

More than three-fourths of energy consumed in the home goes toward heat production (home heating, hot water, and cooking). Half of electricity used in the household (50.4%) is for heat production. 81% of electricity is produced by nuclear power plants or fossil energy (gas, carbon, and oil).

The efficiency of nuclear power plants is around 30%. Here is a closer look at the electricity production and transport process: Fluid is heated to create pressure, and this pressure turns a turbine, which in turn feeds a generator to produce electricity. The resulting electricity is transported to homes, and there it is turned into heat. In terms of energy use, with three transformations and transport involved in the process, heating by electricity is not in our best interest.

Étape 4 - Solar power

The earth is subjected to significant solar radiation of an average power of 173 petawatts (1 PW = 1,015 W), which is 11,500 times the power consumed by humanity.

This solar power is being used a little more each day through the installation of photovoltaic panels. This type of panel has an efficiency of around 15%. There is another more technologically simple system that produces not only electricity but heat. These thermal solar panels have an efficiency of greater than 60%. This means that they produce four times the energy of photovoltaic panels over the same surface area. This is an attractive solution in light of the substantial heating needs in the home.

On a clear day, the power of solar radiation on the surface of the earth is 1,000 W/m2. Even then, the intensity of solar radiation depends greatly on the season. In the summer, the sun is at its highest, or more perpendicular to the earth’s surface, and thus a greater density of rays is captured. On the other hand, in the winter, the sun is at its lowest. Not only is the angle of the sun affected by seasons, but so is day length. In Paris, the day’s length during the winter solstice is a little over 8 hours, while during the summer solstice, the day’s length is more than 16 hours.

Taking into account the power of the sun’s radiation and day length, the solar energy produced on a summer day is almost 6 times greater than that of a winter day (E = P x t).

In order to harness this energy for thermal and electrical use, it is important to orient the panels at an optimum angle for the season, that is, more vertically in the winter and more horizontally in the summer. The fact remains that solar energy is always present, and a system that is very productive during the summer can always be used as a supplement in the winter.

Étape 5 - Heating: the ideal temperature

It is natural that the temperature of a home is higher in the summer than the winter, and that we should dress appropriately for the seasons. Furthermore, it is not necessary for the house to be hot in order to live comfortably. The average temperature of a French home is 20 °C. The ADEME (the French Environment and Energy Management Agency) recommends a temperature of 19 °C in living areas and 16 °C in bedrooms. The difference in heating at 20 °C instead of 19 °C produces an energy overconsumption of 7%.

This can be partly explained scientifically using a simplified version of Fourier’s law, or the law of thermal conduction: J_th = -λ GradT = λ x ∆T/e

Jth : heat flow (W/m²)

λ : thermal conductivity (W/m/K)

∆T : temperature difference between the two sides of the wall (°C or K)

e : thickness of the wall (m)

According to this law, heat flow (that is, heat loss) is proportional to the difference in temperature.

For example, if it is 12 °C outside and a house is heated at 18 °C:

J_th1 = λ x (18-12) / e = λ x 6 / e

If it remains 12 °C outside but a house is heated at 24 °C:

J_th2 = λ x (24-12) / e = λ x 12 / e = 2×J_th1

Regardless of the insulation used and its thickness, if it is 12 °C outside, then the heat loss will be two times greater at 24 °C than at 18 °C.

Étape 6 - Heating: insulation

On average over the year, heating represents two-thirds of household energy consumption at around 11,000 kWh. Considering that heating is only used during the cold season, or about six months of the year, it is a veritable “energy pit,” with about 60 kWh used daily when spread over this period.

A good insulation can reduce heating needs by 80%. There are several ways to insulate a house that vary widely in efficacy and cost.

For example, exterior insulation protects a house from environmental cold and conserves solar energy within heavy construction materials if they are not covered in a thermal insulation. However, this method of insulation is expensive and requires a lot of work to install. And in any case, it isn’t via the walls that the most significant heat loss occurs.

It is important to pay attention to the airtightness of a house, as it is useless to heat air currents even if the house is well insulated. Air currents come primarily from spaces between windows and doors and their frames. A foam seal will significantly limit these currents.

Windows are responsible for 10 to 15% of heat loss. Closing the shutters or using heavy curtains will help you to avoid the need to invest in thicker windows.

It is also important to pay attention to heat bridges, which are weak zones in the building envelope. In these areas, exterior cold is transmitted more rapidly into the interior of a home. The most significant heat bridges are found at junctions between the roof and the walls and between walls and window woodwork. These are the primary areas that should be insulated.

Fourier’s law on thermal conduction is detailed in the previous step. Thermal conduction is the amount of heat that passes from one area to another depending on the type and thickness of the material separating the areas. This conduction depends on the thermal conductivity (λ) of a particular material. The weaker λ is, the more insulating the material is. According to the French regulation RT2012, a material is considered insulating if its thermal conductivity is less than 0.065 W/m/K. Here are some examples of materials that are used in construction:

Material λ (W/m/K) at 20 °C

Brick: 0.84

Cardboard: 0.11

Glass wool: 0.04

Straw: 0.04

Étape 7 - Heating: other options

By this step, much has been improved: air currents have been blocked, the main heat bridges in the building envelope have been insulated, and the target temperature has been decreased by some degrees. Heating needs have thus been significantly reduced. Now, it becomes important to find a new source of heat, or at least an auxiliary source, to reduce direct (i.e., gas, oil) or indirect (electricity) consumption of fossil fuels.

Depending on the type of house and its location, it could be feasible to heat by burning biomass (i.e., wood, pellets, granulated wood) in a woodstove. Biomass stoves (a tutorial on this will be available in December) have an efficiency of greater than 80% and so are very economical in terms of fuel.

Be aware, however, that heating by biomass is not synonymous with environmentalism. In fact, chimneys with an open hearth are one of the most mediocre forms of heating. Reheated air is sucked up the chimney, so the chimney only heats by radiation. The hotter the hearth gets, the greater the draw, and the more air is sucked from inside to the outside. An ordinary hearth can have a draw of 800 to 1,000 m3 of air per hour. The principal use of a chimney is thus reduced to ventilation. Ironically, with a chimney, the more it is heated, the colder the air gets (outside the zone of radiation).

Furthermore, combustion in an open hearth is very incomplete. The fumes that escape through the chimney are unused hydrocarbons, resulting in a shortfall and further pollution.

To summarize, the less fumes there are escaping from a stove, the better the efficiency of the combustion. The lower the temperature of the fumes, the more heat is available for the house.

In order to limit the volume of fuel (biomass, gas, oil) used for heating, it is possible to use solar radiation and its transformation into calories. In winter, the days are shorter and solar radiation is less powerful than in summer, but the available energy is still considerable.

Taking into account the weather, from October to March (the period when heating is used) the sun provides more than 3 kWh/m2 per day in the south of France and more than 2 kWh/m2 in the north. Based on an efficiency of 60%, the energy captured by thermal solar panels would be 2 and 1.3 kWh/m2, respectively.

Étape 8 - Water heaters

Hot water heating represents more than 10% of the total energy consumed annually in a home. The average household consumption is 1,700 kWh per year, or a little less than 5 kWh per day.

Just as with home heating, the first step to take is to well insulate the water heater, the hot water tank, and the pipes coming from it. A new hot water tank of 200 liters has a standing loss of more than 1 kWh per day. Standing loss is the energy related to the decrease in the water's temperature before it is used. So, 20% of the energy consumed daily by this new hot water tank is lost. Insulating the hot water tank will preserve some of this energy. A hot water tank should be cool to the touch; if not, it is simply a radiator and is losing energy in relation to its primary function.

In previous steps we looked at the benefits and limits of thermal solar heating. Home heating needs are inversely proportional to the energy provided by the sun. For water heating, the situation is different: needs are similar throughout the year and are 13 times less than what is needed for home heating in the middle of winter.

The operation of a solar water heater is simple: a heat-carrying fluid passes through insulated tubes that are exposed to the sun. The sun’s radiation heats the fluid, and when the temperature of the fluid exceeds that of the hot water tank, a thermostat opens a circulation valve. The fluid then transfers its calories to the water in the tank.

The water in a hot water tank is heated during the day by the sun. Water has a good thermal inertia, so it will maintain its temperature at night if the tank is insulated.

Thermal solar systems generally have an efficiency greater than 60%, meaning that if the sun radiates 1,000 W/m2, a solar water heater of 1 m2 will generate at least 600 W of heat.

Given the average amount of sunshine in France, 4 m2 of panels is enough to cover daily hot water needs year-round. 3 m2 of panels will cover daily needs 90% of the year except for December, and 2 m2 will cover needs during the hottest half of the year.

In any season, it is possible to have multiple consecutive days without sunshine, in which the water will remain cold. Solar hot water systems are generally paired with electric systems that make up for the deficit during these long cloudy periods.

A low-tech solar hot water system will be documented by the Low-tech Lab in 2018.

Étape 9 - Cooking

Cooking represents about 6% of energy consumed. This is a little less than 1,000 kWh annually or about 2.5 kWh per day.

Overall, from an energy consumption point of view, cooking with gas is the most attractive option. The efficiency of a gas cooker is 60% compared to 90% for induction cookers. However, as seen in the introduction, mains electricity is produced using heat. Taking into account the 70% loss of the power plant and the grid, the energy efficiency of induction cookers falls to 27%.

Mains gas is a natural gas called methane (CH4). It is possible to produce methane on a small scale from organic waste via anaerobic composting. Domestic systems that produce methane are called biodigesters.

To reduce energy consumption in cooking, two simple solutions can be put in place: pot skirts and Norwegian pots. A gas cooker loses a good portion of its energy in heating the air around the pot. A skirt will concentrate the heat of the fire on the spot that needs to be heated. The skirt also insulates the pot, which limits heat loss during and after cooking. This is the same principle with the Norwegian pot, which is used particularly for longer cooks. Once the food has reached the needed temperature, it can be taken off the heat and placed in a well-insulated enclosure. The heat will decrease very gently, possibly over hours, allowing cooking to continue without consuming additional energy. For these two solutions, tutorials will soon be available.

Étape 10 - Specific energy

Specific energy is energy use dedicated to lighting, household appliances, office equipment, and hi-fi. It is the only category of energy use in which the need is for electricity; all other energy used in the home is for heating needs. Currently, this category represents 16.6% of energy consumed. This is a little less than 2,700 kWh per year or about 7 kWh per day.

With the mass arrival of energy efficient bulbs and LEDs, energy consumption related to lighting has greatly decreased. And yet, the consumption of specific energy has doubled since 1990. This is due to the growing number of electric devices such as telephones and computers that are now part of daily life.

To limit specific energy consumption, it is important to not increase the number of devices in the home. Furthermore, devices that are not currently in use are often in sleep mode, which consumes slightly less than 1 W. This 1 W per year used by sleep mode is equal to the amount of energy needed for 4 days of cooking. The energy consumed by multiple devices in sleep mode can be significant.

And finally, there is a phenomenon that may be invisible at an individual level but has a large impact on a national scale: the electric consumption in the evening when a large part of electricity needs are concentrated within a few hours. At that time, everyone returns home and turns on all of their devices (televisions, computers, washing machines, ovens, etc.). The demand is such that the national consumption sees a veritable peak during this period. Since little to no energy can be stored, power plants must provide this energy in real time. French power stations are sized based on this energy demand at the start of the evening.

If electricity consumption were spread out over the day, many electric power plants could be closed. In answer to this need, it is possible to program certain devices to run during the night, or even better, during the day to take advantage of solar photovoltaic panels that are becoming increasingly present.

Étape 11 - Conclusion

Energy consumption in the French household is significant. The first step in individual energy transition is not to change the source of energy and/or the scale of production. The installation of photovoltaic panels or windmills is not economically and ecologically impactful if there is not a significant reduction in energy consumption first.

However, reducing your consumption does not mean depriving yourself of comfort; it means making your home more efficient. Above all else, efficiency is limiting losses. Since more than 70% of energy is consumed in heating, losses can be limited by well insulating the home.

Once these losses are reduced, then it is possible to look for solutions that use less power. The alternatives are numerous and attractive, both low-tech and conventional:

Woodstove Solar heating Solar water heater Bioclimatic architecture Wind power Solar panels Biogas Norwegian pot Pot skirt

Notes et références

https://www.connaissancedesenergies.org/fiche-pedagogique/mix-energetique-de-la-france http://www.statistiques.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/energie-climat/r/consommations-secteur-tous-secteurs.html?tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=21060&cHash=4168b27f68d9955400f2c25b0419095f https://www.ecologique-solidaire.gouv.fr/collection-datalab http://ines.solaire.free.fr/gisesol_1.php# https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conductivit%C3%A9_thermique https://www.connaissancedesenergies.org/fiche-pedagogique/mix-energetique-de-la-france https://www.e-rt2012.fr/explications/conception/explication-architecture-bioclimatique/ http://www.solaire1300.ch/f/technologie-solaire/rayonnement-solaire-delivre-par-heure.asp http://www.ademe.fr/particuliers-eco-citoyens/habitation/renover/isolation/isolation-toit-murs-planchers

English translation : Brianna Lale.

Published

Français

Français English

English Deutsch

Deutsch Español

Español Italiano

Italiano Português

Português