Description

How to have energy-efficient homes

Sommaire

Sommaire

- 1 Description

- 2 Sommaire

- 3 Introduction

- 4 Video d'introduction

- 5 Étape 1 - Energy consumption in France

- 6 Étape 2 - Glossary

- 7 Étape 3 - Electricity and heat in the home

- 8 Étape 4 - Solar power

- 9 Étape 5 - Heating: the ideal temperature

- 10 Étape 6 - Heating: insulation

- 11 Étape 7 - Heating: other options

- 12 Étape 8 - Chauffe-eau

- 13 Étape 9 - Cuisson

- 14 Étape 10 - Energie spécifique

- 15 Étape 11 - Conclusion

- 16 Notes et références

- 17 Commentaires

Introduction

Youtube

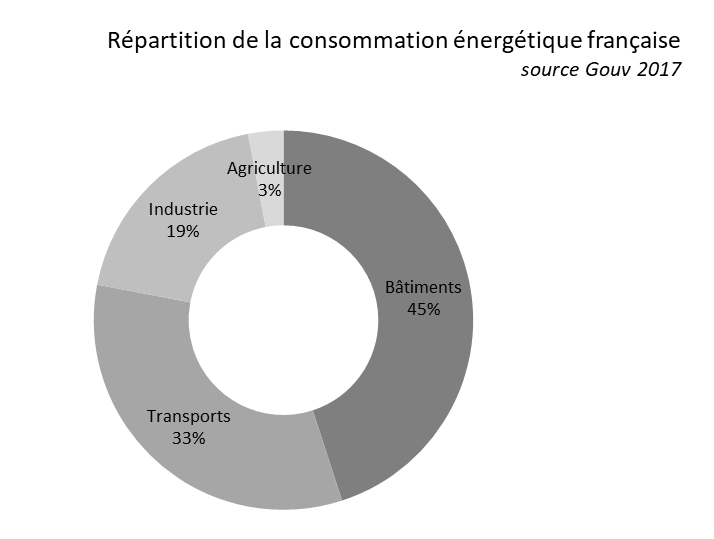

Étape 1 - Energy consumption in France

In France, buildings account for 45% of the total energy consumed, followed by transportation (33%), industry (19%), and agriculture (3%). Two-thirds of the energy consumption in this category comes from housing and one-third from service sector buildings.

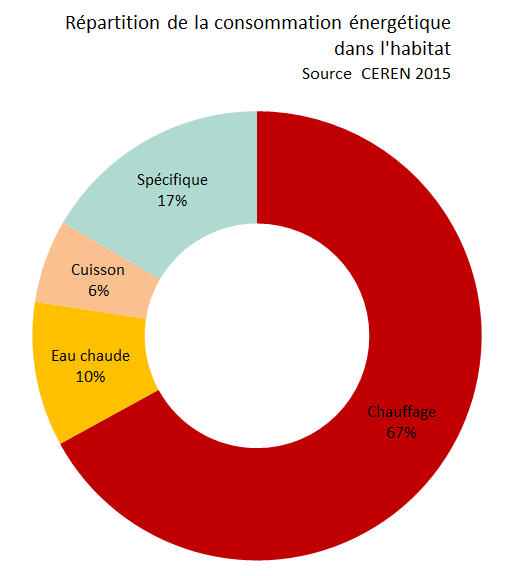

Within the home, in 2013, 67% of consumed energy went toward heating the home, 10.4% toward heating water, and 6% toward cooking. The remaining 16.6% was used for lighting, household appliances, office equipment, and hi-fi, all of which is grouped under the term “specific energy”. The 16,000 kWh consumed by each household costs just over €1,700 per year.

In France, residential heating accounts for a larger portion of the total energy consumed (20.1%) than does industry (19%).

Étape 2 - Glossary

In this tutorial, each category of home energy consumption is explained in detail. The topics of power and energy, which are relatively abstract, are addressed throughout the text.

Here is a brief explanation of these concepts:

Power (P) is measured in watts (W) or kilowatts (kW) Energy (E) is measured in watt-hours (Wh) or kilowatt-hours (kWh)

Power and energy are linked by time: power is the amount of energy per unit time. Power is therefore a rate of energy transfer. P x t = E

Here is an example to illustrate these two closely related concepts:

A cyclist pedaling slowly generates a power of 50 W. If they cycle for an hour, they produce an energy of 50 W x 1 hr = 50 kWh. If they pedal at this same slow speed for two hours, they produce an energy of 50 W x 1 hr = 100 kWh.

The 16,000 kWh produced annually per household thus corresponds to 320,000 hours, or 36 years, of non-stop slow cycling.

If we had to pedal to produce our own energy, how much time would it take? The game “Revolt” shows you the energy consumption of your everyday appliances in hours of cycling: http://la-revolt.org/

Étape 3 - Electricity and heat in the home

More than three-fourths of energy consumed in the home goes toward heat production (home heating, hot water, and cooking). Half of electricity used in the household (50.4%) is for heat production. 81% of electricity is produced by nuclear power plants or fossil energy (gas, carbon, and oil).

The efficiency of nuclear power plants is around 30%. Here is a closer look at the electricity production and transport process: Fluid is heated to create pressure, and this pressure turns a turbine, which in turn feeds a generator to produce electricity. The resulting electricity is transported to homes, and there it is turned into heat. In terms of energy use, with three transformations and transport involved in the process, heating by electricity is not in our best interest.

Étape 4 - Solar power

The earth is subjected to significant solar radiation of an average power of 173 petawatts (1 PW = 1,015 W), which is 11,500 times the power consumed by humanity.

This solar power is being used a little more each day through the installation of photovoltaic panels. This type of panel has an efficiency of around 15%. There is another more technologically simple system that produces not only electricity but heat. These thermal solar panels have an efficiency of greater than 60%. This means that they produce four times the energy of photovoltaic panels over the same surface area. This is an attractive solution in light of the substantial heating needs in the home.

On a clear day, the power of solar radiation on the surface of the earth is 1,000 W/m2. Even then, the intensity of solar radiation depends greatly on the season. In the summer, the sun is at its highest, or more perpendicular to the earth’s surface, and thus a greater density of rays is captured. On the other hand, in the winter, the sun is at its lowest. Not only is the angle of the sun affected by seasons, but so is day length. In Paris, the day’s length during the winter solstice is a little over 8 hours, while during the summer solstice, the day’s length is more than 16 hours.

Taking into account the power of the sun’s radiation and day length, the solar energy produced on a summer day is almost 6 times greater than that of a winter day (E = P x t).

In order to harness this energy for thermal and electrical use, it is important to orient the panels at an optimum angle for the season, that is, more vertically in the winter and more horizontally in the summer. The fact remains that solar energy is always present, and a system that is very productive during the summer can always be used as a supplement in the winter.

Étape 5 - Heating: the ideal temperature

It is natural that the temperature of a home is higher in the summer than the winter, and that we should dress appropriately for the seasons. Furthermore, it is not necessary for the house to be hot in order to live comfortably. The average temperature of a French home is 20 °C. The ADEME (the French Environment and Energy Management Agency) recommends a temperature of 19 °C in living areas and 16 °C in bedrooms. The difference in heating at 20 °C instead of 19 °C produces an energy overconsumption of 7%.

This can be partly explained scientifically using a simplified version of Fourier’s law, or the law of thermal conduction: J_th = -λ GradT = λ x ∆T/e

Jth : heat flow (W/m²)

λ : thermal conductivity (W/m/K)

∆T : temperature difference between the two sides of the wall (°C or K)

e : thickness of the wall (m)

According to this law, heat flow (that is, heat loss) is proportional to the difference in temperature.

For example, if it is 12 °C outside and a house is heated at 18 °C:

J_th1 = λ x (18-12) / e = λ x 6 / e

If it remains 12 °C outside but a house is heated at 24 °C:

J_th2 = λ x (24-12) / e = λ x 12 / e = 2×J_th1

Regardless of the insulation used and its thickness, if it is 12 °C outside, then the heat loss will be two times greater at 24 °C than at 18 °C.

Étape 6 - Heating: insulation

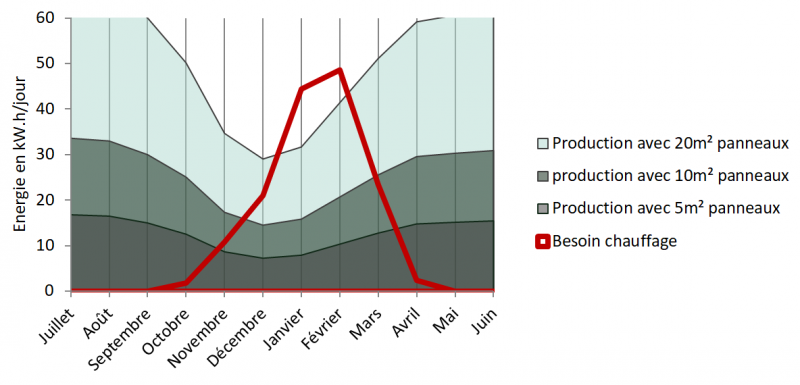

On average over the year, heating represents two-thirds of household energy consumption at around 11,000 kWh. Considering that heating is only used during the cold season, or about six months of the year, it is a veritable “energy pit,” with about 60 kWh used daily when spread over this period.

A good insulation can reduce heating needs by 80%. There are several ways to insulate a house that vary widely in efficacy and cost.

For example, exterior insulation protects a house from environmental cold and conserves solar energy within heavy construction materials if they are not covered in a thermal insulation. However, this method of insulation is expensive and requires a lot of work to install. And in any case, it isn’t via the walls that the most significant heat loss occurs.

It is important to pay attention to the airtightness of a house, as it is useless to heat air currents even if the house is well insulated. Air currents come primarily from spaces between windows and doors and their frames. A foam seal will significantly limit these currents.

Windows are responsible for 10 to 15% of heat loss. Closing the shutters or using heavy curtains will help you to avoid the need to invest in thicker windows.

It is also important to pay attention to heat bridges, which are weak zones in the building envelope. In these areas, exterior cold is transmitted more rapidly into the interior of a home. The most significant heat bridges are found at junctions between the roof and the walls and between walls and window woodwork. These are the primary areas that should be insulated.

Fourier’s law on thermal conduction is detailed in the previous step. Thermal conduction is the amount of heat that passes from one area to another depending on the type and thickness of the material separating the areas. This conduction depends on the thermal conductivity (λ) of a particular material. The weaker λ is, the more insulating the material is. According to the French regulation RT2012, a material is considered insulating if its thermal conductivity is less than 0.065 W/m/K. Here are some examples of materials that are used in construction:

Material λ (W/m/K) at 20 °C

Brick: 0.84

Cardboard: 0.11

Glass wool: 0.04

Straw: 0.04

Étape 7 - Heating: other options

By this step, much has been improved: air currents have been blocked, the main heat bridges in the building envelope have been insulated, and the target temperature has been decreased by some degrees. Heating needs have thus been significantly reduced. Now, it becomes important to find a new source of heat, or at least an auxiliary source, to reduce direct (i.e., gas, oil) or indirect (electricity) consumption of fossil fuels.

Depending on the type of house and its location, it could be feasible to heat by burning biomass (i.e., wood, pellets, granulated wood) in a woodstove. Biomass stoves (a tutorial on this will be available in December) have an efficiency of greater than 80% and so are very economical in terms of fuel.

Be aware, however, that heating by biomass is not synonymous with environmentalism. In fact, chimneys with an open hearth are one of the most mediocre forms of heating. Reheated air is sucked up the chimney, so the chimney only heats by radiation. The hotter the hearth gets, the greater the draw, and the more air is sucked from inside to the outside. An ordinary hearth can have a draw of 800 to 1,000 m3 of air per hour. The principal use of a chimney is thus reduced to ventilation. Ironically, with a chimney, the more it is heated, the colder the air gets (outside the zone of radiation).

Furthermore, combustion in an open hearth is very incomplete. The fumes that escape through the chimney are unused hydrocarbons, resulting in a shortfall and further pollution.

To summarize, the less fumes there are escaping from a stove, the better the efficiency of the combustion. The lower the temperature of the fumes, the more heat is available for the house.

In order to limit the volume of fuel (biomass, gas, oil) used for heating, it is possible to use solar radiation and its transformation into calories. In winter, the days are shorter and solar radiation is less powerful than in summer, but the available energy is still considerable.

En prenant en compte la météorologie, d’octobre à mars, période d’utilisation du chauffage, le soleil fournit plus de 3 kWh/m² par jour dans le sud de la France, plus de 2 kW.h/m² dans le nord. En prenant un rendement de 60%, les énergies captées par un panneau solaire thermique seraient respectivement de 2 et 1,3 kW.h/m²

Étape 8 - Chauffe-eau

Le chauffage de l’eau chaude sanitaire représente plus de 10% de l’énergie totale consommée à l’année dans un logement. La consommation moyenne d’un foyer est d’environ 1 700 kW.h par an soit un peu moins de 5 kW.h par jour.

Comme pour le chauffage du logement, la première action à réaliser est de bien isoler sa chaudière, son chauffe-eau et les tuyaux qui en sortent. Un chauffe-eau neuf de 200 litres a des pertes statiques de plus d’ 1 kW.h par jour. Les pertes statiques sont l’énergie liée à la diminution de la température de l’eau sans qu’elle soit consommée. 20% de la consommation quotidienne est perdue. Sur-isoler le ballon permet d’économiser une part conséquente de l’énergie. Quand on touche un chauffe-eau, il doit être froid, sinon c’est un radiateur, il perd de l’énergie par rapport à sa fonction première.

Précédemment étaient étudiés les intérêts et limites du chauffage solaire thermique. Les besoins en chauffage sont inversement proportionnels à l’énergie fournie par le soleil. Pour l’eau, la situation est bien différente : les besoins sont similaires toute l’année et 13 fois moins forts que le chauffage en plein hiver.

Le fonctionnement des chauffe-eau solaires est simple : un fluide caloporteur (qui transporte la chaleur) passe dans des tubes isolés exposés idéalement au soleil. Avec le rayonnement, le fluide chauffe ; quand la température du fluide est supérieure à celle du ballon d’eau chaude, un thermostat ouvre la vanne de circulation. Le fluide caloporteur transfère ses calories à l’eau sanitaire.

L'eau du ballon chauffe dans la journée, avec le soleil. L’eau a une bonne inertie thermique, elle gardera sa température pendant la nuit si le ballon est isolé.

Les systèmes solaires thermiques ont un rendement en général supérieur à 60%, c’est-à-dire que si le soleil rayonne 1 000 W/m², un chauffe-eau solaire de 1 m² générera au moins 600 W de chaleur.

Avec l’ensoleillement moyen en France, 4 m² de panneaux permettent de couvrir les besoins quotidiens toute l’année ; 3 m² de panneaux permettent de couvrir les besoins pendant 90% de l’année, décembre excepté; 2 m² couvrent les besoins en eau chaude pendant la moitié la plus chaude de l’année.

Quelle que soit la saison, il est possible d’avoir plusieurs jours consécutifs sans soleil. L’eau restera froide. Les systèmes de chauffe-eau solaires sont en général couplés avec un système électrique qui prend le relai pendant les longues périodes nuageuses.

Un système de chauffe-eau solaire low-tech sera documenté par le Low-tech Lab en 2018.

Étape 9 - Cuisson

La cuisson représente environ 6% de l’énergie consommée. C’est un peu moins de 1 000 kWh sur l’année soit environ 2,5 kWh par jour.

Globalement, d’un point de vue énergétique, la cuisson au gaz est la plus intéressante. L’efficacité d’une gazinière est de 60%, contre 90% pour des plaques à induction. Mais, comme vu en introduction, l’électricité du réseau est produite avec de la chaleur. Si on prend en compte les 70% de pertes de la centrale et du réseau, le rendement énergétique de l’induction chute à 27%.

Le gaz naturel distribué dans le réseau est du méthane (CH4). Il est possible d’en produire à petite échelle à partir de déchets organiques via un compostage anaérobique. Les systèmes domestiques permettant la production de méthane sont appelés méthaniseurs ou biodigesteurs.

Pour réduire la consommation propre à la cuisson, deux solutions simples peuvent être mises en place : les jupes isolantes et la marmite norvégienne. Une gazinière perd une bonne partie de son énergie en chauffant l’air autour de la casserole. Une jupe permet de concentrer la chaleur du feu sur la zone à chauffer. La jupe isole également les champs de la casserole, cela permet de limiter les pertes de chaleur pendant et après la cuisson. C’est également le principe de la marmite norvégienne, particulièrement utilisée pour les cuissons longues. Une fois le plat monté à température, on le retire du feu pour le placer dans une enceinte très bien isolée. La chaleur va descendre très doucement, possiblement pendant des heures, permettant à la cuisson de continuer sans consommer d’énergie additionnelle. Pour ces deux solutions, des tutoriels seront bientôt disponibles.

Étape 10 - Energie spécifique

L’énergie spécifique est l’énergie dédiée à la lumière, l’équipement électroménager, la bureautique et la hi-fi. C’est la seule énergie pour laquelle le besoin est de l'électricité. Toutes les autres énergies de l'habitat sont des besoins de chaleur. Elle représente aujourd’hui 16,6% de l’énergie consommée. C’est un peu moins de 2 700 kW.h sur l’année soit environ 7 kW.h par jour.

Avec l’arrivée massive des lampes à économie d’énergie et des LED, la consommation consacrée à la lumière a fortement diminué. Cependant, la consommation d’énergie spécifique a doublé depuis 1990. En cause, le nombre croissant d’appareils électriques et électroniques, comme les téléphones et ordinateurs qui habitent le quotidien.

Pour limiter sa consommation spécifique, il faut faire attention à ne pas multiplier les appareils. De plus, les appareils non utilisés sont souvent en veille, avec une consommation légèrement inférieure à 1 W. Mais une veille d’un Watt sur l’année correspond à l’énergie nécessaire pour cuisiner pendant 4 jours. L’énergie consommée par plusieurs appareils en veille peut être conséquente.

Pour finir, bien qu’invisible individuellement mais avec un très fort impact à l’échelle nationale : la consommation électrique en fin de journée, où une grande partie des besoins énergétiques sont concentrés sur quelques heures. Chacun rentre chez soi et allume tous ses appareils (téléviseurs, ordinateurs, machine à laver, cuisinière, etc). La demande est telle que la consommation nationale connaît un véritable pic sur cette période. L’énergie n’étant pas ou peu stockable, les centrales doivent fournir cette énergie en direct. Le parc électrique français est dimensionné par cette demande en énergie, en début de soirée.

Si la consommation électrique était lissée sur la journée, plusieurs centrales électriques pourraient être fermées. Pour répartir ce besoin, il est possible de programmer certains appareils pour la nuit ou, encore mieux, en journée, profitant du solaire photovoltaïque de plus en plus présent.

Étape 11 - Conclusion

La consommation énergétique dans le logement français est importante. La première étape à réaliser dans la transition énergétique individuelle n’est pas le changement de source d'énergie et/ou d’échelle. L’installation de panneaux photovoltaïques ou d’éoliennes n’est pas intéressante économiquement et écologiquement parlant s’il n’y a pas eu une importante réduction de la consommation énergétique avant.

Mais réduire sa consommation ce n’est pas se priver ou même perdre du confort. C’est rendre son habitat plus efficace. L'efficacité, c’est avant tout limiter ses pertes. Plus de 70% de l'énergie consommée étant du chauffage, limiter ses pertes c’est bien isoler son logement.

Une fois les pertes réduites il est possibles de s’orienter vers des solutions moins puissantes. Dans ces conditions les alternatives intéressantes sont nombreuses, en low-tech, ou conventionnelles :

- poêle à bois

- chauffage solaire

- chauffe-eau solaire

- architecture bioclimatique

- éolienne

- panneaux solaires

- biogaz

- marmite norvégienne

- jupe isolante

Notes et références

- https://www.connaissancedesenergies.org/fiche-pedagogique/mix-energetique-de-la-france

- http://www.statistiques.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/energie-climat/r/consommations-secteur-tous-secteurs.html?tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=21060&cHash=4168b27f68d9955400f2c25b0419095f

- https://www.ecologique-solidaire.gouv.fr/collection-datalab

- http://ines.solaire.free.fr/gisesol_1.php#

- https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conductivit%C3%A9_thermique

- https://www.connaissancedesenergies.org/fiche-pedagogique/mix-energetique-de-la-france

- https://www.e-rt2012.fr/explications/conception/explication-architecture-bioclimatique/

- http://www.solaire1300.ch/f/technologie-solaire/rayonnement-solaire-delivre-par-heure.asp

- http://www.ademe.fr/particuliers-eco-citoyens/habitation/renover/isolation/isolation-toit-murs-planchers

Published

Français

Français English

English Deutsch

Deutsch Español

Español Italiano

Italiano Português

Português